Hydrogen essential to a clean energy future: Rising to the challenge

The energy industry is rising to the challenge of a hydrogen economy. For many, it is essential for a clean energy future. Some three quarters (73%) of senior energy professionals say Paris Agreement targets will not be possible without a large-scale hydrogen economy and a similar share (74%), say there is no way to achieve a zero-carbon economy by 2050 without hydrogen.

Reading time 5 minutes

These are the findings of DNV’s latest hydrogen research: Rising to the Challenge of a Hydrogen Economy. This explores the outlook for the emerging hydrogen economy, from production through to consumption, drawing on a survey of more than 1,100 senior energy professionals.

From another perspective, DNV’s Energy Transition Outlook (ETO), our independent forecast of the world’s energy system to 2050, finds that the world will not achieve a widescale hydrogen economy by 2050. Our analysis indicates that hydrogen will only start to scale as an energy carrier from the late 2030s, growing strongly in the 2040s to reach 5% of global energy demand in 2050, albeit with large regional variations – with hydrogen meeting 12% of final energy demand in Europe. However, our best-estimate forecast also shows that the world will miss the targets of the Paris Agreement. Cumulative emissions will exhaust the 1.5°C budget in 2029, 2°C budget in 2053 and indicate 2.3°C global warming by end of the century.

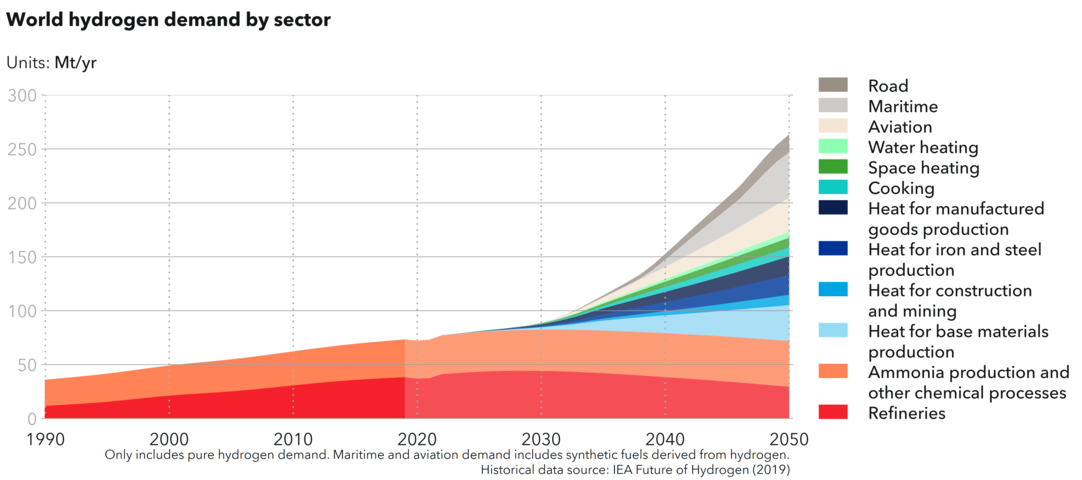

These two findings from our ETO are closely connected and support the industry view that hydrogen is essential to a clean energy future. The issue lies in hard-to-abate sectors that cannot be easily decarbonised through electrification, including aviation, maritime, long-haul trucking and large parts of heavy industry.

Hard-to-abate sectors are currently responsible for around 35% of global CO2 emissions and progress in reducing these emissions is stubbornly slow. We forecast that these hard-to-abate sectors will reduce their emissions by just 33% by 2050, while all other sectors combined will reduce emissions by 55%. We find that hydrogen and hydrogen-derivates are the most promising solution to decarbonise these sectors, in addition to providing energy storage to support the huge growth in renewables and electrification required for a deeply decarbonised energy system.

Rising to the challenge

The challenge for the hydrogen economy is not in the ambition, but in changing the timeline: from hydrogen on the horison to hydrogen in our homes, businesses, and transport systems.

Three quarters (74%) of energy professionals say that the outlook for a hydrogen economy improved significantly in the past 12 months, while two thirds (67%) expect this will continue in the next 12 months.

Ambitions and the rate of change in the hydrogen economy are sky high, leading some to question whether hydrogen goals are realistic. However, more than just outlook and ambition, hydrogen is rapidly rising up the agenda in terms of revenue and spending.

Almost half (44%) of energy companies involved in producing and distributing hydrogen and the supply chain expect it to account for more than a tenth of their revenue by 2025, rising to 73% of companies by 2030. This is up significantly from just 8% of the companies in the survey today.

On the other side of this new energy value chain, 33% of hydrogen consumers expect hydrogen to represent more than a tenth of their organisation’s energy or feedstock spending by 2025, rising to 57% by 2030. This is up from just 9% today.

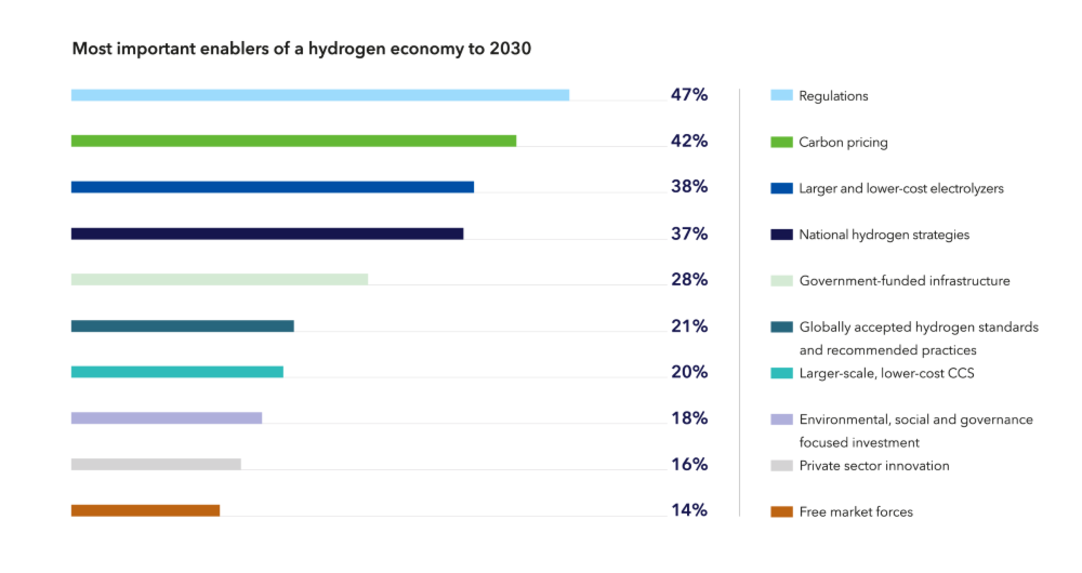

While much of the required hydrogen technology is proven, hydrogen value chains require significant development. The scale to meet the expected demand and applications will require new ideas, processes, and models. The right regulations are deemed the most powerful enabler of a hydrogen economy, followed by carbon pricing.

Key regulatory issues include: safety, such as the safety distances for hydrogen stations; rules for hydrogen and ammonia fuelled ships; injection and blending of hydrogen into natural gas transmission systems; subsurface storage of hydrogen, such as in salt caverns; quantity and pressure limitations in road transport; greenhouse gas footprint requirements for low carbon hydrogen; and connecting electrolysers and fuel cells to the electricity grid.

Financing will also be key. DNV’s research Financing the Energy Transition raises the issue that hydrogen opportunities are currently long-term, low-return, and seemingly high-risk. Financiers are unlikely to jump at them without significant government support to create certainty and provide more direct support through subsidies or an effective carbon price.

On the debate between green and blue hydrogen, just under half believe that more blue hydrogen will be produced and consumed than green hydrogen in 2030, while 35% have the opposite view. Crucially, the majority of energy professionals (77%) believe that both blue and green hydrogen need to work in synergy to successfully scale the hydrogen economy. This is also DNV’s view and the view from our ETO research. Green hydrogen will dominate in the long run, but blue hydrogen will be key to scaling the hydrogen economy. We forecast a roughly 80/20 split between blue and green hydrogen in 2050. At this point, we expect two thirds of green hydrogen to be produced via electrolysis from dedicated off-grid renewables, with the remaining third produced from cheap grid electricity.

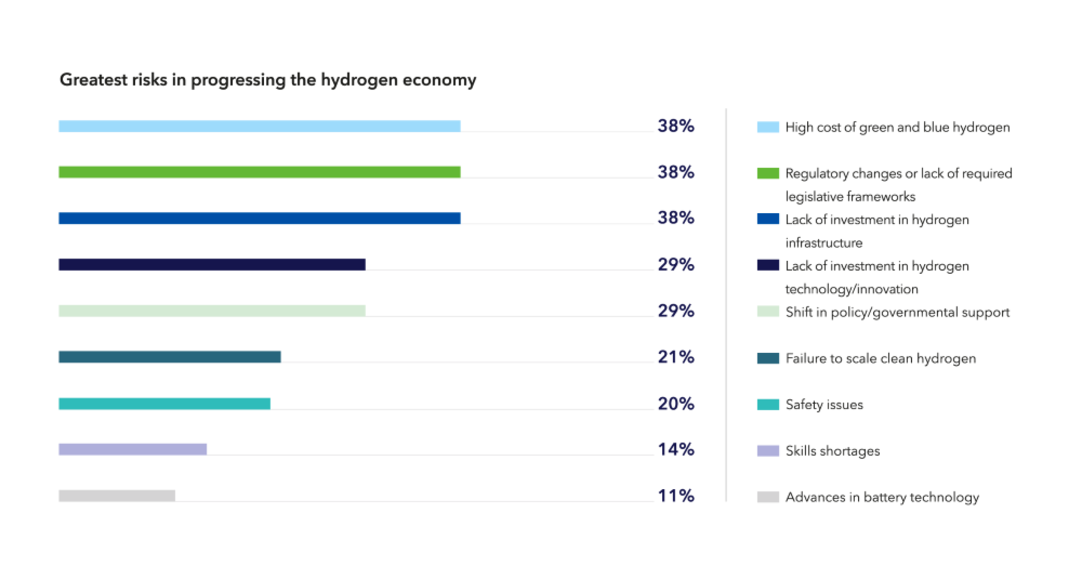

The energy industry is aware of the significant challenges involved in rapidly adopting hydrogen. Some 71% of senior energy professionals believe current hydrogen ambitions underestimate the practical limitations and barriers to adoption. Infrastructure and cost are two of the biggest hurdles. For those currently not invested or involved in hydrogen, a lack of infrastructure is the top reason why they focused elsewhere. Some 78% of the energy industry believes repurposing existing infrastructure will be essential to develop a large-scale hydrogen economy.

Nevertheless, around 43% of the industry believe that the majority of national and organisational hydrogen goals are realistic. This could be seen as quite high, considering how ambitious some of those targets are and the challenges involved.

To progress to the stage where societies and industry can enjoy the benefits of hydrogen at scale, all stakeholders will need immediate focus on proving safety, enabling infrastructure, scaling production and incentivising value chains through policy.

Article written by Jørg Aarnes, Global Segment Lead – Hydrogen and CCS, DNV