The Hong Kong Convention finally set to enter into force – a gamechanger?

With the recent accessions by Liberia and Bangladesh, the Hong Kong Convention on ship recycling, which was adopted in 2009, will finally enter into force on 26 June 2025. On 30 November 2023 there was a further breakthrough by Pakistan’s accession, which means that all major recycling states have now committed to the Convention. What will be the practical implications? How will the Convention mesh with the existing regulations?

Lesetid 6 minutter

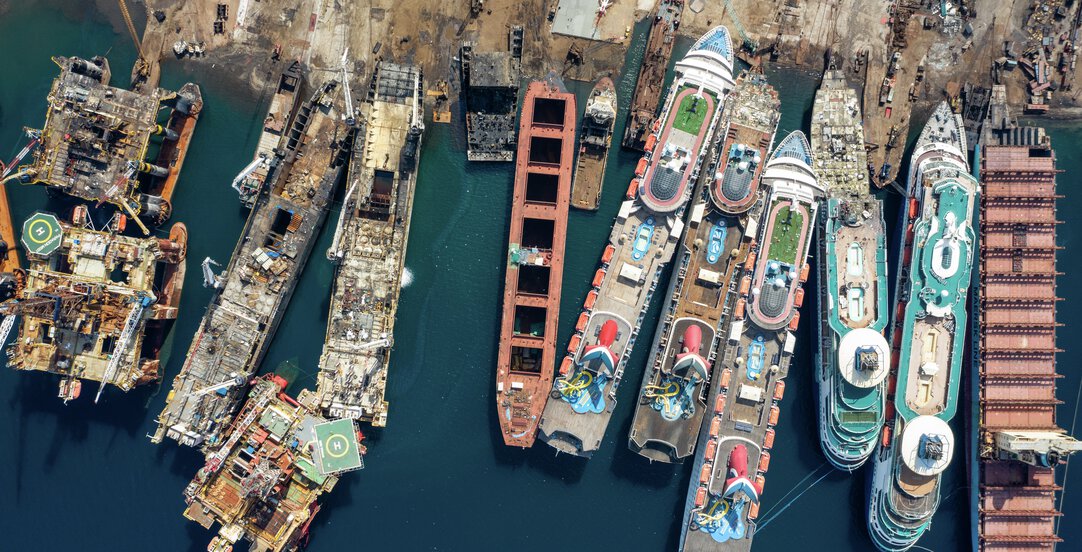

Ship recycling practices have been raising concerns for years, particularly in South Asia, where ships have often been rammed up on beaches at high tide and broken up in the tidal zone in ways that are unsafe for the workers and releases pollutants to the environment.

Hong Kong Convention

The aim of the Hong Kong Convention is to ensure the safe and environmentally sound ship recycling on a global basis.

It adopts a cradle-to-grave approach by setting out extensive regulations that apply from the time a ship is designed until it is recycled.

The Convention applies to ships flagged in contracting states, which are required to carry an Inventory of Hazardous Materials (IHM) and will only be allowed to be recycled at authorised facilities. For the purposes of the Convention, ships include not only conventional ships but also floating platforms, jackups, FPSOs and FSOs.

The Convention also applies to recycling facilities located in contracting states, which must be authorised by national authorities. The facilities are required to have in place a Ship Recycling Facility Plan (SRFP) and also, in each project, to develop a Ship-Specific Recycling Plan (SRP). National authorities will be responsible for ensuring that recycling facilities under their jurisdiction comply with the requirements of the Convention.

EU Ship Recycling Regulation

The EU believed that the entry into force of the Hong Kong Convention was taking too long and that it was not strict enough. It therefore enacted the EU Ship Recycling Regulation in 2013, which implemented the Hong Kong Convention on an EU/EEA level. It also introduced additional requirements, most importantly that EU/EEA flagged vessels shall only be recycled at facilities which are approved by the EU Commission and placed on the so-called European List. So far, the EU Commission has not approved any facilities in South Asia, which means that EU/EEA flagged vessels cannot be recycled in for example India, Bangladesh or Pakistan.

The Ship Recycling Regulation also has certain additional downstream waste management requirements and health and safety requirements. These stricter requirements will be allowed to continue when the Hong Kong Convention enters into force, since the Convention only sets out minimum requirements and does not prevent national or regional regulations from imposing stricter rules. This will impact both ships flagged in the EU/EEA and recycling facilities located in the EU/EEA.

EU Waste Shipment Regulation and Basel regime

An additional set of regulations is the EU Waste Shipment Regulation, which was enacted by the EU in 2006, and which implemented the Basel Convention 1989 and the Basel Ban Amendment 1995.

The Basel Convention regulates the movements of hazardous waste across international borders and its disposal. It applies to ships which are destined for recycling and requires consent from the export, import and transit state.

The Basel Ban Amendment goes further and prohibits export to non-OECD states.

The export ban, as implemented in the EU Waste Shipment Regulation, means that a non-EU/EEA flagged ship would be prohibited from being exported to a non-OECD state if it was in EU/EEA waters when the decision to scrap the ship was taken.

These rules are very strictly enforced, as has been seen particularly in the Netherlands, as well as in Norway where the owner of the “Tide Carrier” was sentenced to 6 months in prison for having assisted a cash buyer in attempting to export the vessel from Norway for recycling at a beach in Gadani, Pakistan, which is outside the OECD.

Hong Kong Convention vs. Basel

India, Bangladesh and Pakistan have acceded to the Hong Kong Convention and will no doubt have Hong Kong compliant facilities available by the time the Convention comes into force. These countries are not OECD countries. A question will be whether the Basel Ban Amendment and implementing domestic legislation would mean that a non-EU/EEA flagged vessel would be prevented from being exported from the EU/EEA to an authorised yard in India, Bangladesh or Pakistan.

The general view, including that of the EU, has been that the Basel Ban Amendment would not prevent a vessel from being exported from an OECD or EU/EEA country to a yard in a non-OECD country like India, Bangladesh or Pakistan for recycling, provided that the yard is authorised by national authorities under the Hong Kong Convention or is on the European List. This is because the Hong Kong Convention and the EU Ship Recycling Regulation will supersede the Basel Convention if they impose environmentally sound waste disposal standards at least equivalent to those under the Basel Convention.

Therefore, the EU is in principle positive to including yards for example in India or Bangladesh as long as they satisfy the requirements under the EU Ship Recycling Regulation. However, this has been questioned by several NGOs and others who suggest that the Basel Ban Amendment would in fact bar the possibility of exporting ships from OECD or EU/EEA countries for recycling in a non-OECD country, even if the yard is Hong Kong authorised or on the European List.

The EU is currently considering whether to address these issues by revising the regulations.

Impact of the Hong Kong Convention

It will be a significant milestone to finally have a binding set of international regulations aimed at ensuring safe and sustainable ship recycling.

With Pakistan also having acceded to the Convention, all major ship recycling states (except China) are parties to the Convention. Together, Bangladesh, India and Turkey recycle about 80 per cent of the world’s recycled ships in terms of gross tonnage. When including Pakistan, this figure is about 95 per cent. Therefore, Pakistan’s accession will be very important to the success of the Convention.

There are still only 23 contracting states. Flag states have been particularly reluctant to becoming parties to the Convention. However, the important commitment by the major recycling states means that many of the remaining flag states are expected soon to follow and accede to the Convention.

Standards have already been raised significantly, particularly at yards in India and Bangladesh. In the interim period before the Convention finally comes into force, it is expected that this trend will continue.

That Pakistan is now committed to making its yards compliant by the time the Convention enters into force in 2025 is very positive. There were questions as to whether Pakistan would feel pressured to accede to compete or whether it would operate outside the Convention, offering higher scrap prices which for some owners could make up for the legal and reputational risks associated with sending ships to non-compliant yards.

In many ways it has been good that the EU has been leading the way and managed to accelerate the adoption of the Hong Kong Convention, as well as the Basel regime. However, the regulatory landscape has become very complex with several layers of global, regional and national rules.

Moreover, the regional EU rules have not been very effective since it has been too easy to circumvent them by reflagging or trading outside of the EU/EEA when making the recycling decision.

Global regulations are necessary to tackle global problems.

The entry into force of the Hong Kong Convention represents an important commitment by the international community towards sustainable and responsible ship dismantling practices, especially as it ensures important and binding minimum standards applicable to yards in the countries where the problems related to recycling have been greatest.

Whether the Hong Kong Convention will achieve the goal of safe and environmentally friendly recycling, will to a large extent depend on how the Convention is applied by national authorities when it comes to authorising facilities and enforcing compliance with the Convention.

Shipowners and other stakeholders are in any event faced with the challenge of navigating through the complicated regulatory landscape. Compliance should be carefully considered, as there are significant reputational and legal risks related to non-compliance.